Overview

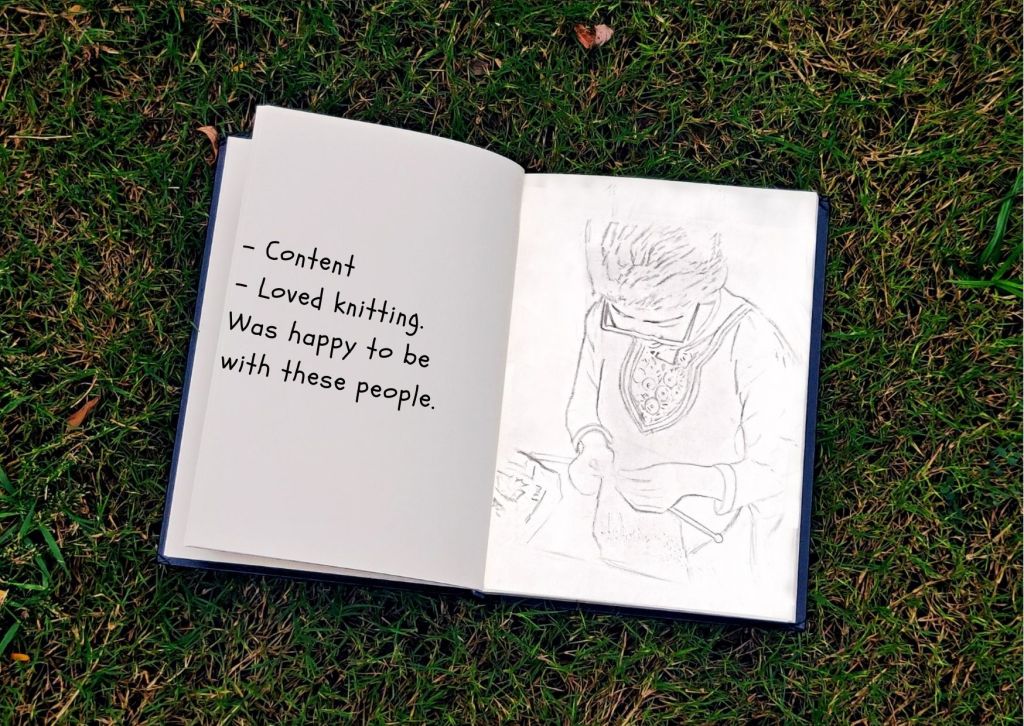

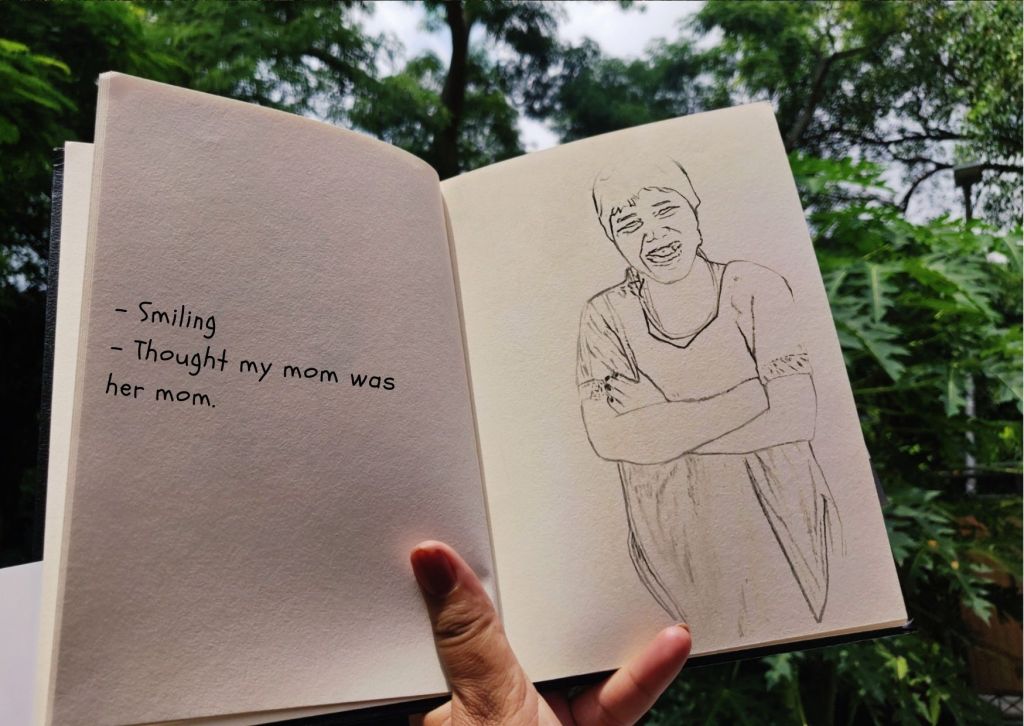

This is an interview with a head nurse, at a home for the abandoned ladies—Jivodaya Ashralayam. Their motto is “To Rehabilitate – To Reconstruct – To Restore.” To everyone’s surprise, this old age home has women from all over India with various intellectual disabilities. You will witness people helping each other with daily routine tasks. It might take you some time to get hold of things at first; you could witness a woman knitting or sitting in anger because the nurse denied her request to phone home. Some of them are aware of the fact that they have been abandoned by their families while the rest are in denial.

In this piece, you will be sharing a space with people who don’t remember who they are, whom they belong to, why they are here and how to go about their lives from here on. While reading further, keep this “identity crisis” in mind because to us, they are different, but to each other, they are not; they are just as normal as anyone else can be.

INTERVIEWED BY: AISHWARYA VYAS

EDITED BY: RASHMITHA MUNIANDI

ARTWORK BY: AISHWARYA VYAS

Where do these people come from? How do you choose them to live under one roof?

“We are getting them pre-approved by the police and court. They all are different types of mentally disabled people; few are schizophrenic or violent, but everyone differs. Some are extremely aggressive and some are calm, some are adjustable and some take time.”

This means that at some point in time, they had a family and a home or a permanent address for that matter. They were dutifully fulfilling their roles in a “perfect” society as a mother or a daughter or a sister. They had an identity, a religion, a nationality, a name, and citizenship that they were aware of. It’s not just these aspects but their academic talents or any other sorts of experiences have also turned into dust now.

So all of the people you have brought in so far have been abandoned somewhere? Did any of them get traced back or taken back to their original families?

“Only two to three patients until now were sent from home because their families couldn’t afford to take care of them. Sometimes families come to visit them, otherwise, they simply tell us not to contact them in the near future.

Some of them were left at the hospitals and a few of them got stranded away from their homes on their own. We report to the missing squads in such cases and further to the CBI. Again, only two or three of these women were helped by the CBI to return to their families.”

It was hard for me to accept that people can choose to leave a person once their disability is recognised. It may feel like a burden to keep up with all the costs of medications or appointments, and not every poor family in India can do it. But abandoning a differently- abled is an option—I did not know.

Do you have records of how many patients were brought in this year or last year? Can I have a look at them to be able to decipher some of the exact terms of their medical conditions?

“Yes, we have the records. We don’t have the authority to share their personal information. We have the license and hence only the staff can refer to the documents. You can talk to the patients and get an idea of how they feel. They will tell you that they want to go home but they don’t know where their home is; maybe it is in Nepal or Kashmir—they don’t remember their addresses.”

Talking to the patients about it was difficult, or perhaps I did not have the courage. Our lives comprise all the experiences and memories that led us on this journey. What if something takes those memories away and everything you have ever achieved as a student or a son or a daughter or a mother gets erased. That’s the kind of life these women are living now, as they have no identity and no former connections with their pasts. They are getting on with life like a living archive. The personal interest that caught me to work in this direction was that they have no gist of all the memories they have lost. I have all the memories stacked right in my head as compared to them.

So how many people are here right now?

“Around 62, with most in their old age. With these types of patients, you cannot expect much work out of them—just normal chores. But at times, even the daily chores mean nothing to them. One day, they are doing it, and the next day, the chores mean nothing to them. Sometimes they do the opposite of their daily routines, sometimes they obediently follow.”

How do you connect with them? Also, are there some patients who have speaking or hearing impairment?

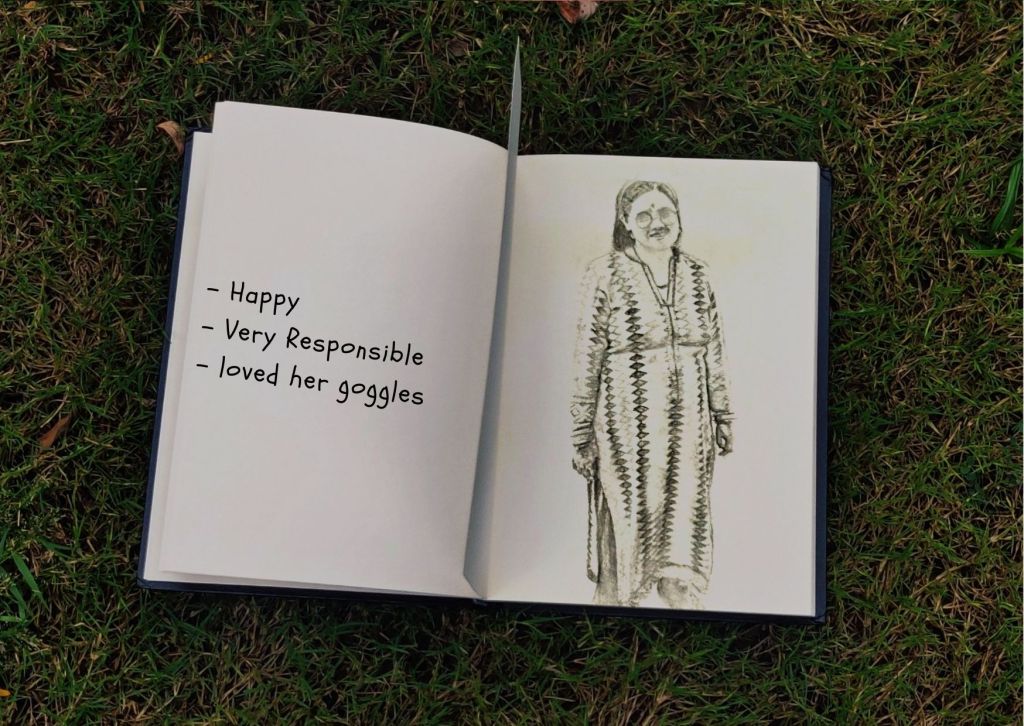

“How do we connect with them? We work here to make this a home. This is their home. We live here. Sometimes it’s difficult to manage but we have some ways to converse with them. We communicate through expressions, and actually one of them is the happiest here and she is very expressive. She is my personal favorite. We also have the right medications if required.”

Kudos to the spirit of these women who are selflessly working towards making these women belong to a new family. All the people with intellectual-disability call the nurses “mummy” no matter what their age is. This gives a sense of how things work here despite so much diversity.

So who provides for their medication?

“We are getting medicines from the government. Especially from the psychiatric department. We are taking them almost every two months from the hospital in Dwarka. Usually, we maintain their files and if there is any change in behaviour or health condition, we report to the hospital and they come by.”

Do the patients feel any different or are they oblivious to this?

“For them, they are normal. Only we identify their problem. They don’t even know how old they are, since we don’t have any records like a birth certificate or anything. We give a certain age to them by guessing and do the same with their names sometimes. So, an 85-year old is the oldest here. And yes they are oblivious.”

Being oblivious seems easier with so much going on. When in reality, we are trying to fight against the stigmas or stereotypes to not call someone with adjectives like “mentally retarded,” these women are making a living and finding comfort in each other’s warmth. One person here teaches maths and science to the neighbourhood kids because they are too poor to afford tuition; another is in charge of looking after the visitors.

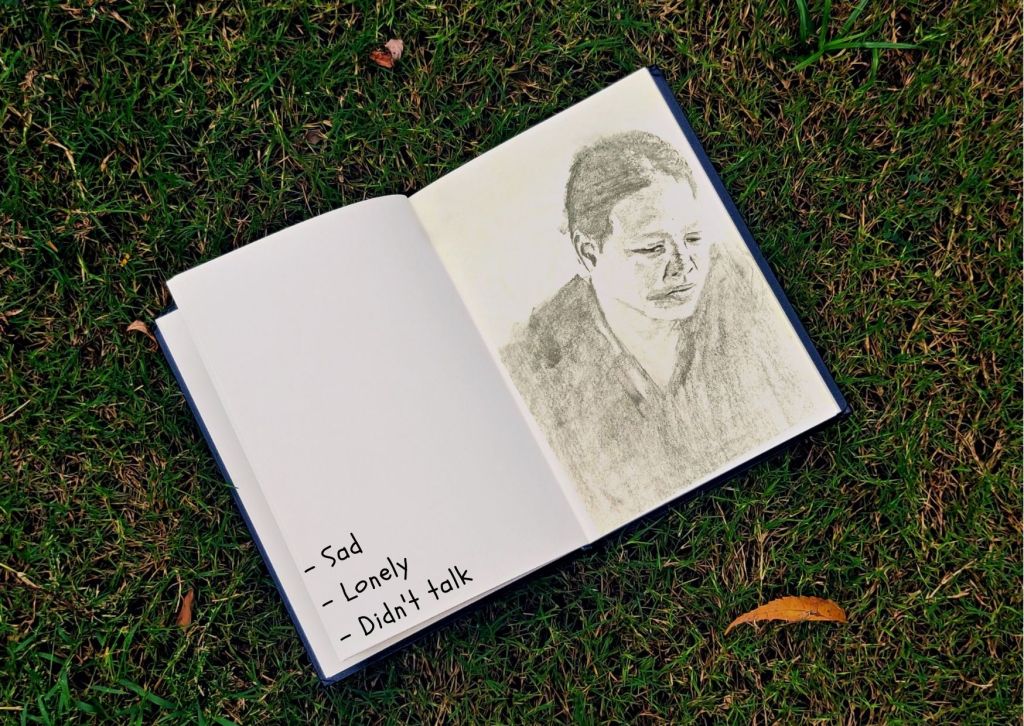

Do they get emotional sometimes? Do they feel the absence of any loved one?

“Some days they are happy and some days they are sad. They wake up every day and start their daily routine. They have their timetable. They have prayer, yoga, knitting, flower making, and cutting vegetables. One of them also teaches primary school children. They just keep busy or surround themselves with people. They do get emotional but not because of the absence of anyone as they don’t remember anyone.”

They wake up to their family.

Are there sufficient funds? Are only the three of you sisters able to manage all the patients?

“Government is supporting us a little, which is not enough, but we get funds from outside. Then there are people like you who help us to keep them content and fulfilled. Psychiatric medicine is not cheap and they are not available everywhere without prescriptions. It’s not just psychiatric medicines that we need; some patients have high BP or thyroid or some other condition. We have helpers, a driver, and a car in case of emergencies.”

Everyone was aware of the casual visitors that come for some time and then leave; they keep up with their chores. I also remember one woman who actually showed me the jail-like cell and a mortuary room while giving me a tour of the facility. She was more afraid of the cell than any other room. The nurse further told me that if someone gets an attack or is out of control, they have to lock her in order to protect others and herself from self-damage.

Have you ever raised the question of insufficiency to the government?

They don’t give any intake. They don’t give the pensions of the patients even, because they don’t have their identity cards or adhaar card. According to the government, these people just don’t exist because they don’t count as citizens due to the loss of their identity. We don’t know what religion they belong to or what language they speak. One of them here was a successful dentist, but after her illness, there was no one in her family left and that’s how she is here. Nobody bothers. If it was our own blood, then one feels the need to fight. Otherwise nothing. Duniya aise hi hai.”

What about their grooming?

“Their hair specifically is really short because if they fight, the hair gets all strangled. They still don’t feel any different though with the boy cut. They cannot do it (get a haircut) without being angry or being stubborn but they know that we love them; we ask them quietly with affection to settle down and they cooperate. That is what Jesus taught us. He is the giver, we are just the mediator. They brush and clean themselves in their daily routines.”

Hair is typically considered an important part of feminine identity in society, but in here it doesn’t count as one.

What kind of training do you have in handling such people? Since how long have you been here? Do the sisters keep changing?

“We all have done our graduation in medic in psychiatry and counseling, or sociology. We have an idea of how to give different therapies like speech therapy and how to treat a kid. Once, we received a little two-year-old baby who was also mentally unstable.

Yes, we keep getting transferred to different places, be it a school, a village, or a hospital; it depends on the need or kind of services required at that place. I have been here for four years. We get transferred to different states too.”

I remember visiting that baby; it was hard to see him abandoned here. He was happy with all the attention he got here from all the women. He was soon shifted to another facility. It was amazing to see how these people accept everyone with open hands.

It’s not necessary that all the lives here have a happy ending. As you have said, they wake up with each other and they suddenly realize that someone is missing. How do you help them settle back?

“Yes, they immediately realize that someone is missing and they inform us like “mummy ye nahi hai”; in fact, two or three people get angry at night and hide themselves in the dark, so the others help them come back to bed. They move freely because it’s their home, and there are no restrictions. They are also welcoming to new patients by telling them how to do the chores.

At times of menstrual cycles, they help each other with the cloth to use. We cannot buy so many sanitary napkins because every day eleven to twelve people are going through it. We have to lock the premises so that no one gets out.”

Does anyone else approach you for the funds, like NGOs?

“Yes, local people approach us. They are helpful but in the case of the NGOs, they have some other purpose. It’s like they make a show of their work through these people. Ten or twenty people come, they take photos and leave. It’s just a show for social media. They don’t have this facility; through our patients, they portray their problems and move on.”

What are the problematic areas at present?

“We don’t have a proper sewage system. After every two months, our toilets are full. So we have to call the sewage cleaner truck which costs around 2000 rupees every month. We tried approaching one minister, and he got some money waved off for every month’s trip. We also don’t have the facility of pure drinking water, since pipelines are still not available in this area. So we have to buy motor power which costs around 15000 rupees.”